|

Naamal De Silva Whose stories are on your shelf? Who's stories do you follow on social media? What personal stories about the environment have influenced your work and your life? It is nearly 4am on Wednesday and I’ve been awake for awhile. I feel consumed. Last week, I felt consumed by the news and by social media. The #blacklivesmatter protests are painful and hopeful and transformative. Between the pandemic and these protests, life and society appear to be changing so rapidly. There is such uncertainty. I am terrified that the stories that have become newly visible to so many will once again be covered over, that our progress will erode away into nearly nothing. I care deeply about diversity, both cultural and biological. My entire life, I have felt that much of what I value is invisible to many people, at least to most people with power to create change. In this moment, if feels like that might change. I have such hope that we are about to move towards a time of justice, greater equality, protection for the vulnerable, and greater care for each other and for the planet. I have hope, but I am afraid that I will end up heartbroken.

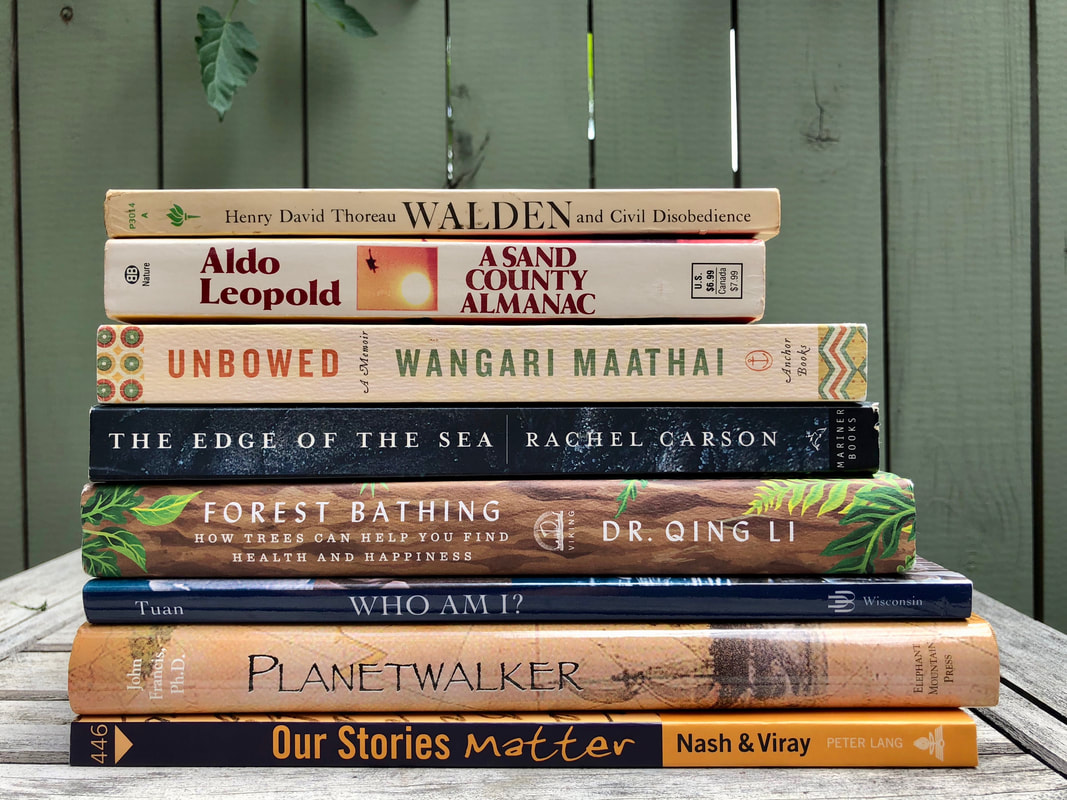

Last year, witnessing the global climate protests and Greta Thunberg’s rise, I felt hopeful that we were moving forward towards broader understanding about environmental problems, and that our understanding would extend towards an understanding of the unjust impacts of climate change. I had hope that the anger of children would move us more rapidly towards solutions and towards justice. I hoped that, within and outside of the environmental field, we would see more stories of young people of all colors, nations, orientations, shapes, abilities, and religions. Since the climate strikes have become digital because of the pandemic, it feels as though a lot of that that energy and attention have dissipated. We cannot afford to look away. Climate change and biodiversity loss pose threats to our existence, just as police brutality poses a threat to the existence of black people in America. It will take all of us to address systemic racism in America. It will take all of us to protect vulnerable groups of people throughout the world. It will take all of us to address the climate crisis, species extinction, and plastic pollution. It will take all of us to ensure that the impacts of social and environmental problems are distributed equitably throughout society. To engage and enrage and inspire all of us, it will take the individual stories and emotion and the passionate dedication of a diversity of people. The stories of these people need to be more visible. Throughout my adult life, I have sought stories of the diversity of people working for the environment. I knew that the environmental field was not only composed of the white and the privileged – it only felt that way because the brown and poor were invisible. I searched for stories, but I felt that I was sifting through sand. I looked for these stories in books, in the mainstream media, and in academic journals. I did not find nearly enough. A few years ago, I found far more through social media. I sifted, and I started following accounts of people who spoke out about how they belonged in nature – accounts like those of Rue Mapp and Jenny Bruso and of organizations like Outdoor Afro, Unlikely Hikers, and Melanin Basecamp. I learned about more stories by attending events and meeting people. I found even more through my dissertation research and reading. I gathered some stories by chance - my path to Maya Hall’s story started with trying on a jacket at a Patagonia store. I started a writing group for Mayla and people shared unexpected things. Finding these people and their stories felt like validation. I started Mayla because I felt the need to gather and amplify these voice – the voices of diverse people who care for the environment. I intended to include the stories of white people alongside the stories of black, brown, and indigenous people from all over the world. However, the stories of white people always felt easier to find. I wanted all the stories, but I was looking for the ones that appeared to be rare. That is why I feel consumed right now. Over the past week, it has been so much easier to find stories of diversity. I have been digging deeper into the lives and stories of those who are #blackinnature. These stories bring me joy, even when they express anger. They are some of the stories for which I have been searching my entire life, and suddenly, it feels like I am inundated. I can’t seem to get enough. They are stories that feel intimately familiar, and yet, they are not my stories. They are the stories of people who surrounded me as I was growing up, of people who were friends or who are friends. They are the stories of authors who have influenced my life and how I see the world. They are stories of people who share my skin color but not my history. I have many stories of feeling invisible, and a few stories of feeling like I stand out or don’t belong simply based on my color. The stories of black Americans help me feel more visible. At the same time, they highlight my differences. When I am alone in nature, there have been times when I felt unsafe because I am a woman. There are very few instances where I felt unsafe because I am brown. I can recall one summer afternoon in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, my white husband and I were walking along a forested creek, where a group of white men pulled up with lots of beer and a confederate flag flying from the back of their pickup truck. They did not say anything to us, but as an interracial couple, we felt intimidated, and we left. They took up the space we ceded. As we left, we noticed a large Latino family on the far side of the pickup truck; they were the only other people there and they did not give up their right to enjoy time in nature. Maybe we did not need to do so either. There are far more instances when I have felt protected by my invisibility. In high school, I studied a lot and followed most rules, but I would leave if I felt that I was not learning anything. Two of my history teachers were often missing; my world geography teacher read a newspaper during class while a group of boys played poker in the back of the room. I felt a sense of freedom in leaving, but little fear about cutting class. As I left the building, there would always be police cars around my mostly black school in my mostly white neighborhood. Police officers would be standing by these cars, and I saw them stop black and Latino teenagers. They mostly stopped boys, but a few girls too. They would return these students to the school building. They never once stopped me – they hardly ever even looked at me. It was as though they could not see me, as though my glasses and my South Asian face and my silence were a shield. In those moments, invisibility felt like power. In my career, I have felt at times that invisibility has held me back. I have, at times, attributed disparities in pay or recognition to my gender or my age or my skin color. Certainly, there have been many times in conference rooms where I have made a point that the rest of the people in the room ignored until it was repeated by a white man. There have also been many times when white men have amplified my voice and supported my work, whether through empowering me to publish articles or through opening doors that might otherwise remain closed despite my education and experience. I am a brown woman in conservation – sometimes that makes me invisible and at other times it makes me stand out. Nevertheless, I have not had to think about whether my hairstyle would keep me from a promotion. I have never wondered whether I might be arrested or possibly killed for walking in a park. Amidst the deluge of stories this week, I keep returning to that of Christian Cooper, whose care for the lives and wellbeing of birds posed a direct threat to his own life and wellbeing. We all needed to hear his story, but not just the story of his encounter with Amy Cooper. We all need to hear stories of the diversity of people who care about nature. It is through stories that we make meaning of what is happening in the world. Through stories, we process loss, whether it is the loss of a human life at the hands of the police, or of a nearly extinct shark at the hands of fishermen. We need the stories of the people who resist injustice and who halt extinction. We need MORE stories of black and brown and indigenous and white scientists and activists and innovators and farmers who are passionate and visionary. We need to feel their pain and anger and joy, to hear about their ancestors and home places and sources of inspiration. We need their creative solutions and unique perspectives. We need to see the ways in which racism and injustice limit our collective access to creativity, innovation, and care for the earth. We need their stories and their work to be visible so that, together, we can envision a future that is both just and sustainable.

4 Comments

Naamal De Silva This mural by Aniekan Udofia is outside the Rumsey Aquatic Center in the Eastern Market Neighborhood of Washington, DC. It has inspired me for years. After feeling increasingly hopeless yesterday, I woke up this morning enthusiastic about centering the voices of African Americans in a series of blog posts – I thought of specific stories and of specific people who have inspired and influenced me throughout my life. I have so many ideas. I want to amplify black voices and have wanted to do so for many years. But what does that mean? What does that statement truly require from me and from other people and institutions intending to make that commitment? What are the costs, what are we willing to invest, and what are some ways to move beyond the hashtags? The hashtag #amplifyblackvoices resonates strongly with me, but the hashtag by itself will not create systemic change.

To move beyond the hashtags, we have to think first about why we want to amplify black voices. Is it because of personal guilt and pain about racism? Is it to seek sources of reconciliation and healing and joy? Is it to find different ways of knowing or to find hidden solutions? Whose voices, in particular, do we want to amplify? How will such amplification benefit those people? How might we benefit? Reflection and reading always help me work through such questions. Next, consider time - our own time and especially the time of people whose voices we intend to amplify. I identify as a brown woman, an American, and an immigrant, a Sri Lankan; I am so much more than those labels, but I am not African American. If I want to find and share a range of black perspectives, I am asking for the time and energy of people who might have very little of both. If we are not ourselves African American or part of the African diaspora, amplifying black voices could include sharing what black people have already created and shared publicly. If we want more than that, and in many cases, we should want more, then we are asking for a commitment of time and creativity and brain power. If we intend to amplify voices other than the comparatively few who already have a platform from which to speak, we will have to request interviews or essays or poems or songs or videos. Over the past several years, I have been doing just that. I have been asking a diversity of people for their personal stories about protecting and connecting with nature. I have been searching for people with diverse backgrounds and experiences because I believe that a more complex and nuanced understanding of the environment and each other will lead to more productive and meaningful work. I have asked for the perspectives of those who differ from me in terms of ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexuality, class, and myriad other facets of identity and experience. In asking for their stories, I have not provided any financial compensation to any of these individuals - not because I did not want to or did not think to do so, but because I had no funding to offer. Despite that lack of compensation, I’ve benefited from their ideas and their stories have enriched my life and work. Some people I asked have wondered what they had to share that would be of value to others. They have told me that what they do is not special or unusual. They have told me that they are only volunteers, not professionals. They have told me that they are not experts. In each of those cases, I can’t help feeling that there is a long history of silencing and invisibility behind those beliefs – a personal history but likely also an intergenerational history. In those cases, I have found wealth and class and education to be bigger barriers than race. What can we do? In some cases, nothing - not everyone wants to stand on a stage. In other cases, find and hire those passionate and inspiring individuals so that they become professionals rather than volunteers. Invest in education and in creating opportunities for more black, indigenous, and brown people to become experts. Invest in management training and in leadership training. Many of the people whom I asked for stories responded with enthusiasm. They have attended writing group meetings and salons, spoken in the class I teach at George Washington University, mentored young people, exchanged emails, or had conversations with me about what they hope to share in the future. I’ve interviewed people for my dissertation, for my blog, and for my consulting work. These individuals have told me that these interactions have been meaningful. Is that enough? Despite their enthusiasm and generosity, most of the people I’ve asked are tired and have little time outside of work and parenting and other obligations to reflect or write or complete blog posts. Despite years of such conversations, very few of their stories end up on my website. As has become glaringly visible this week, African Americans tired of carrying the additional and heavy burden of systemic racism. So many people of all races who do environmental and social justice work are tired. They are burdened by enormous obstacles, public apathy, and limited resources. Many also carry the burdens of being unpaid or underpaid. They are tired because, in addition to their internships or volunteer work, they need to take on additional jobs in retail or restaurants that do not adequately utilize their skills and education. If, as in too many cases, they cannot move on to better paid roles or rely on their families for financial support, they may need to abandon their efforts to protect society and nature. Many leaders of organizations devoted to social justice, poverty alleviation, education, and the environment cannot afford to adequately compensate their employees and have to compete for scarce resources. If they are people of color, and especially if they are black or indigenous, they are far less likely to win. They are tired. We are tired. I am tired. It should not be such a struggle to meaningfully engage a diversity of voices and perspectives. We should not have to be at a point where we need to say that black lives matter or to implore each other to amplify black voices. This exhaustion is not sustainable, and because of exhaustion, so many people do not publicly celebrate their successes or share their perspectives. So what, then, is my own commitment to amplifying black voices? I do not yet have the funding to pay for articles or interns for Mayla. I can commit to writing more about what I have seen and heard about the experiences of African Americans. I can ask to share what people have already written on their own blogs and social media pages and websites. I can continue to encourage black people to share their own stories. I can do all of these things and more. But, how do I address the broader forces that maintain the silence and invisibility of black and brown voices? Phrased another way, how do I amplify black voices and share diverse stories without contributing to exploitation and without myself being exploited? Part of what exhausted me yesterday was seeing a wave of posts on Instagram where African Americans in the arts and in the environmental field highlighted the importance of being financially compensated for intellectual property and creativity. In those posts, I couldn’t help but notice the stain of a legacy of exploitation that stretches back centuries. How can we move beyond exploitation? Financial compensation is only part of the work to amplify black voices, but it is an important part of the work. I often hesitate to ask people for their stories or their involvement with Mayla because I want to be able to compensate them financially. I have no interns or staff or fellows, though I could find many who would effectively expand the work that I do. If people make too little money through their work, how will they have the creative freedom to share their stories? In America, there is abundant research that shows that black people (on average) make less than white people do, and that difference is more stark for black women. On average, if a white man and a black woman begin working on January 1st, the black woman will need to work throughout year and into August of the following year to earn what the white man makes at the end of December. This is a systemic problem and requires institutional work on the part of nonprofits, corporations, and the government. The exploitation is not purely financial. Within the environmental and international development fields, the photographic exploitation of black and brown bodies is particularly prevalent. I have written about this before using my own experiences. I continue to be amazed at the ability of conservation organizations to raise money for the work of primarily white people by using the smiling images of poor black and brown people. This needs to change. Conservation and development photographers need to ask permission of black and brown parents before photographing their children; if those parents are not with their children because they are plowing their fields, they might reconsider whether they capture the image at all. These photographers need to ask for the stories and names of the people they photograph so that we no longer end up with broad general statements about entire groups of people. It is time that environmental and development organizations finally move away from the myth of the noble savage. We need to amplify specific and individual voices of the black and brown and indigenous and poor. In particular, I believe we must amplify the diverse voices of people working to improve the environment. Next time you are creating your annual report, consider replacing that unknown smiling black face with the specific story of a black or brown person who is a colleague or partner. Consider hiring a black or brown photographer to take those photographs so that you have something better than a grainy image taken in a conference room. Better yet, include black or brown staff members and board members and partners in creating the vision and mission and strategy and metrics that guide your work. These are many very specific ways in which organizations can move from hashtags to empowerment. How do we ethically amplify black voices? Find diverse stories, including by and about black people. Read widely. Reflect, question, and share. Engage a diversity of people in your work. Include black people in creating your vision, your goals, and your proposed actions.Compensate black people for their time and input. Invest in their personal goals. Ask them to share their own stories. Repeat. Let’s continue to call for amplifying black voices and for amplifying the voices of indigenous people and countless others who have been left out of the conversation and who remain invisible. Let’s also focus on systemic change that prevents further exploitation. Resources The articles I referenced in this post, in order: Racial bias in philanthropic funding for environmental and social justice - an article by Cheryl Dorsey, Peter Kim, Cora Daniels, Lyell Sakaue & Britt Savage in Stanford Social Innovation Review. The wage gap by gender and race - an article by Sonam Sheth, Shayanne Gal and Madison Hoff View people as individuals rather than representatives of their ethnicity or nationality – an article by me on the Mayla website A history of racism in the environmental movement – an article in Vice by Julian Brave NoiseCat. A brief list of relevant blogs and websites and social media pages by and/or about black voices for the environment: Outdoor Afro and founder Rue Mapp Our Climate Voices and work on grassroots climate solutions Echoing Green and president Cheryl Dorsey Green 2.0 and Whitney Thome The Anacostia Community Museum and especially work by Katrina Lashley on Women’s Environmental Leadership The Black & Project by Amanda Bonam These are some of the people and organizations that have been on my mind this week, but there are so many more, and I strongly believe that it is our responsibility to look beyond the few stories and organizations that are most visible. We must look for and amplify diverse people and stories relevant to the places where we live and work. Since the problems and solutions are local and global, we must also push ourselves to move ever outward from familiar places and perspectives. Look inward – at your own heart and your own past experiences and your own community. Look outward – to the stories of black and indigenous people in other parts of your state or province, your nation, and in other nations. By, Naamal De Silva Two years ago, my brain was buzzing with hashtags about nature and people. I came up with a list, and a good friend added an important one – #WeAreNature. When we feel viscerally that we are part of nature, we want to care for all species as we care for our families, pets, friends, and selves - after all, we are all related. When we perceive ourselves as part of nature, we also see more connections to other humans. In 2019, it feels like fewer and fewer of us notice that we are part of this ecological web of interconnectedness. More and more of us are tangled in the worldwide web. More and more of us live in cities. We are increasingly disconnected from nature, and seeing ourselves as nature could move us back towards connection. More recently, I’ve also been considering how we perceive each other. In particular, I’ve been thinking about how conservationists perceive people. I am a conservationist. I am keenly aware of how this work grows daily in importance as our world becomes hotter and more crowded. At the same time, I am uncomfortable with the social history of conservation. The history, traditions, and methods of conservation facilitate another type of separation between humans and nature. This separation was deliberate, and persists today in far less conscious and obvious ways. In this view, there are people, who are largely responsible for environmental degradation. We are the ones who own corporations, drive cars, and eat mangos in the middle of winter. Sure, there are the few who are vegan, protect coral reefs, and don’t use straws. But, we humans are still responsible and need to feel guilty. Then, there is nature. Nature is awe-inspiring, colorful, fragile, and desperately in need of saving. Nature includes coral reefs, polar bears, poison dart frogs, and majestic redwoods. Nature also includes indigenous people and those who maintain traditional lifestyles. Looking back a few hundred years, this distinction shows up when Europeans collected a few live humans along with their tobacco plants and vividly colored birds. Explorers took these specimens home to impress the royals and nobles who paid for their expeditions. The royals would show them off to their friends. Today, photographers collect images of lush rainforests, vividly colored birds, and smiling villagers to raise money for nonprofit conservation or development organizations. On social media, these photographs tend to have captions or accompanying narratives. In these stories, richer, whiter, more urban people almost always have names. They have first names and last names, and often titles too. They are often depicted with the tools of their trade – camera, clipboard, binoculars. By contrast, the stories almost always refer to indigenous and traditional people by tribe or village. Bejeweled Maasai men look nobly into the distance. Tibetan children smile with impossibly rosy cheeks. A Tanzanian or Tibetan tour guide might be allowed a first name. Their clothes are western, modern – they are human, but barely. I have taken photos of Maasai men and of Tibetan children. When I traveled to distant lands, it was easy to be struck by the beauty of people, their surroundings, and the ways in which they decorate themselves. I was entranced by their differences and their similarities to myself. Throughout the world, lives and places and traditions seemed to be changing so quickly. Photography was one way to hold on and to bear witness to what was fading away. I have taken photos of bare-chested teenagers in Papua New Guinea. I do not know their names. I wish I did. At the time I took the photos of these teenagers, I knew that I would never share these photos without cropping them. But, I did use one or two cropped images of their lovely, smiling faces in PowerPoint presentations. My presentations had more to do with protecting rainforests and reefs than with the lived experiences of these girls. These girls were minors, and I certainly did not have signed waivers from their parents. I did not even know where their parents were. All I saw when I got off a plane in Alotau was a group of excited teenagers wearing skirts made of grasses, their faces painted and weapons at the ready. They danced to welcome people arriving for a conservation conference. They were proud of their performance and pleased to be photographed. I saw them then as I see them now: as teenagers, with all the excitement and anxieties that come with rapid shifts in identity and appearance. I did not see them as “nature,” but I did not talk with them or write down their names. This was 2008. Cameras tended to be digital, but social media was in its infancy. I will not be sharing those photos on this blog post. A few months later, someone in the communications department of my organization categorized me as nature based on a photo. In the photo, I am smiling, squatting in front of the rough wooden boards of a small building, mud on my pants and a flower tucked behind my ear. It’s a portrait that I love, taken by a friend who knew me well. My friend, William Crosse, took this photo on the same trip where I took the photos of the teenagers. He had contributed some of his images to the photo bank of the organization where we both worked at the time. Generally, these images were used without captions on the website, on presentations, and in brochures. This particular image was used in an internal slide show and in a brochure. The brochure was where the sorting happened, and it happened in the captions, which featured some named people (the conservationists, the heroes, the saviors) and some nameless people (the recipients of conservation largesse, those living in harmony with nature, as nature). I was nameless. I was not one of those conservation heroes. Someone had cropped out my digital camera. My smile and my brown skin were being used to sell an old idea about saving faraway, exotic nature and faraway, exotic people. I could imagine a caption for that photo of me: “In the face of accelerating climate change, women from tropical islands struggle to maintain their traditional way of life. Rising sea levels threaten to wash away their ancestral lands. [Insert name of environment or development organization] helps by teaching them how to farm seaweed.” A caption like that would be sort of true. I was born on a tropical island. My grandmother's family lived for generations on coastal land in the village of Thiranagama. That land holds some of my earliest memories, of digging my toes into wet sand, searching for elusive clams while holding on against the tug of the waves. I wonder at times whether rising seas will wash away that land. But, in this particular photo, I was on a very different tropical island. I don’t struggle to maintain a traditional way of life – I was born in one capital city (Colombo) and grew up in another (Washington, DC).  In the face of accelerating climate change, women from tropical islands struggle to maintain their traditional way of life. Rising sea levels threaten to wash away their ancestral lands. [Insert name of environmental or development organization] helps by teaching them how to farm seaweed. Photo by William Crosse. My friend took another photo of me on that trip. In it, I have a camera in front of my face, with a lens large enough to block out my features. I’m sitting on a boat in the middle of a river, with hazy tropical hills behind me. I could imagine a caption for this photo too. “Dr. Naamal De Silva, on a field trip in rural Papua New Guinea in 2008. At the time, she worked with numerous partners to identify globally important sites, species, and landscapes.” Labels are powerful. Labels delineate belonging and community. However, through this very delineation of group identity, they inevitably exclude. Each of us has many labels. The labels we use for ourselves are rarely exactly the labels that others assign to us. Labels also change over time.

Our names, by contrast, are relatively stable. Our names highlight our individuality, and they are markers of our humanity. Taking away our names takes away part of our humanity. Slavery in the United States provides a powerful example of that. I recently saw what might be the first known portrait of a slave, a young woman known only as Flora. While it is a lovely, biophilic name, it is unlikely that “Flora” was what her parents named her, or what she chose for herself. Similarly, during the holocaust, nazis at concentration camps replaced the names of Jews, Roma people, and others with tattooed numbers. Stripping away names, stripping away humanity, facilitates acts of unthinkable brutality. Independent journalism and bearing witness can help prevent or halt genocide and other horrors based on sorting and exclusion. Photography is a vital type of storytelling, and since life is continually unfolding, sometimes it is impossible to ask for names. Sometimes, naming people can compromise their safety or their ability to speak openly. I understand that. And, I believe that conservation photography is vital, since we will not feel moved to protect what we cannot see. While not directly attributable to climate change, a portrait of a starving polar bear made the consequences of climate change feel more viscerally relevant and immediate for billions of people. Portraits of a giant Indonesian bee and a lonely Bolivian toad brought the world’s attention to species that we considered to be lost forever. Portraits of individual humans can similarly highlight diversity, beauty, peril, joy, vulnerability, power, and so much more. Recognizing all of this, I still believe that we can all do better in showcasing people as both part of nature and as humans. Portraits of people should highlight individuals as subjects and not objects – we should feature their humanity alongside their connections to nature. Including full names whenever possible helps showcase both humanity and agency. |

Curating Hope features the personal stories of diverse people who protect nature. Together, we can envision a more sustainable future.Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed