|

Ariel Trahan and Naamal De Silva Ariel at work on the Anacostia River. Photo courtesy of Ariel Trahan. Naamal: Waterways help connect us to nature and to each other. During the fall of 2016, as part of my doctoral dissertation research, I spent some time observing and talking to Ariel Trahan about her environmental education work on and for the Anacostia River. This story is adapted from that research. I view experiential environmental education as a powerful but massively underfunded solution to environmental injustice.

Ariel grew up in a tree house just outside a factory town called Bay City, in Michigan. The town had “a number of automobile plants; there's a lot of blue-collar workers. And then the factories closed down, and so it's so now it's really dropped in population.” Her mother, a photographer, and her father, a builder, “are definitely outdoor people.” When they were about 25, they built the house she grew up in. “It's kind of like a tree house. It's up on stilts, made out of wood, and it's out in the woods. Inside, it's really open and there's a lot of unfinished wood.” Ariel has deep family connections to certain places. After attending a Catholic elementary school, and a public middle school, she went to a boarding school in Troy, New York that her mother, her grandmother, a total of about five generations of ancestors had attended. Growing up, she spent a lot of weekends at her paternal great grandparents’ cabin in Northern Michigan. Her siblings and cousins had a fort in the woods there, away from the cabin, where they would go to play. There was a river where they “would spend hours swimming, fishing, canoeing, just being in the water.” They “would walk across the shallow river and around the island in the middle.” Perhaps because of these experiences and the influence of her parents, she and her siblings all work within the boundary between environment and education. “I have an older brother who's a teacher; he started a garden at his school. And I have an older sister who used to be a teacher and then went back to school for a master’s in environmental education. And now, she works at a school as their agriculture program coordinator.” Ariel went to a small liberal arts school, Macalester College in Minnesota and maintained a strong relationship with nature. “We had a big outing club. We would always go up to the north shore in Minnesota, go camping, canoeing there.” She started out as a History major but added Environmental Studies after being inspired by a geology class called “Rivers of the World.” After college, she worked for a few years at the camp she had attended since turning eight, then at a residential outdoor education center in New Hampshire called Nature’s Classroom. She took a break to travel for six months with her two best friends to Belize, Guatemala and Mexico, where they worked on organic farms (“woofing”). After that, she moved to Washington, D.C. to be closer to friends and a more urban work life. Ariel: I loved living in New Hampshire but it was so isolated. And also, it was great to have these kids come and have this experience out in the woods, but I started to feel more and more that it was perpetuating this idea that nature is separate from you. And then you go back to school and nature is gone, no more nature. That really started to bother me, and so I really wanted to try urban environmental education. She first applied for a position with another waterway-based nonprofit in Washington, which turned out to have been filled, but the staff there recommended an opening at the Anacostia Watershed Society. She got the job and gained an unusual introduction to city. Ariel: When I started working here, everything that I learned about DC was from the perspective of the river, which is a completely different way from how most people are introduced to the city. When I first lived here, I knew where the Arboretum was, and I knew where Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens was, and I knew where Benning Road was, based on the river, but I no concept of how to get any of them from the road. Ariel has been there ever since, and finds her work to provide an ideal balance between community and solitude. Ariel: My co-workers and I go kayaking in the morning sometimes…I feel like I have this unique existence where I live in the city, but I am away from people and buildings a lot of the time. It's perfect for me. A Year on the Water: Waterway-Based Environmental Education During my interview with Ariel in 2016, I asked her to describe a typical workday, and she replied that her work varies over the year based on what is happening in schools and on the river. This summary of her work is in Ariel’s voice. January and February are definitely quieter months inside: a lot of grant writing, reporting, work plans, and preparing for the year ahead. Starting at about the end of February, we start preparing a lot of materials for class visits. In the spring, one of our really big initiatives is Rice Rangers, where we put grow lights in the classrooms and kids grow wild rice seedlings. We deliver materials to each school, and when we deliver them, we facilitate an activity with the kids. The other thing we do during the spring is to help kids raise American shad in the classroom. Just like with the rice, we provide them with equipment; we deliver the hatcheries and do class visits to support that work. Every day, we get here really early, load all the stuff in the truck, drive to the schools, unloading all the stuff, set everything up, and work with the kids. Around April, we start taking students out on the water. Our boating season is St. Patrick's Day to Thanksgiving. That is our rule of thumb, but we try not to schedule too much in March because you just never know. We start in earnest in April and we take people out on the pontoon boat and in canoes. In May, we start doing plantings, so the kids who started the plants in the classroom begin bringing them out and planting them along the river. The planting window for the wetlands is between about April 15th and July 15th. We can only do so many plantings with kids each year because it has to be low tide during the middle of the day, on a weekday. So it's a really small window; there are only about ten days that are school days with low tide between about ten and one. On those ten days, we usually try to have four or five classes out per day. It’s a lot. The kids put their boots on, bring their plants out, and take a nature hike. We try to include a third activity too, so we bring in different partners. The Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center does a bird-banding demo. Or, we have somebody from the Anacostia Aquatic Resources Center show them different animals. That way, they plant rice, but there's something more too. The students who raised shad all come out on the same day and release the fish into the river. We facilitate that. In May and June, we also teach the school-based activities for RiverSmart Schools, where students help install stormwater retrofits at their schools and we do lessons with them. We get them to use those installations to study and understand the plantings and make connections to the river. It's kind of this jigsaw puzzle. Some days, I do class visits, some days I facilitate a planting, some days I take students on a boat trip. And, there are always a million meetings. During the summer, I spend a lot of time on the water, getting people out. We do school-based programs for kids, but we also have trips for the public. That's one of the biggest things with the Anacostia, is just getting people out there. It seems like a small, basic thing, but it makes a huge difference. In June and July, we are on the water almost every day, taking people out. August is definitely slower, with planning for the school year, but things pick up again in September. In the fall, we do a program called SONG (Saving Our Native Grasslands), where we work on restoring meadows as buffers along the different tributaries and along the river itself. So, we do a lot of seed collection with the kids during field trips. They collect seeds, and then they go on the boat that same day. We will take them to a spot where we are working to restore the meadows, and they spread the seeds. They also build some kind of habitat structures: sometimes it's birdhouses and sometimes we make mason bee houses. And, we also collect wetland seeds in the fall, and bring both adults and kids out to collect seeds. Naamal: This yearly rhythm of work has stayed with me, and since the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve often thought about how 2020 must have been different: a year without the excited babble of young voices on the water, without small hands collecting wild rice seeds.

2 Comments

Naamal De Silva This weekend, I hosted the first in a new Mayla workshop series, “Hope Through Nature, Hope Within.” These writing workshops are meant to create a little space for reflection, writing and sharing. In the face of societal and personal losses and traumas, personal writing in community might be a way to heal ourselves and mend the world in small ways.

With ten people, the workshop was intimate enough to stay together the entire time. The participants were from different contexts in my personal and professional life; there were a couple of people I did not know personally. They joined the Zoom call from four countries across three continents, with roots in at least six countries on four continents. For me, the ability to connect virtually across boundaries and time zones has been one of the brightest parts of a dark time. The workshop was just what I hoped for – a space of sharing sorrow, joy, memories, and inspiration. To begin, we shared where we were right now, one worry, and one place that brought us joy during childhood. To me, this initiated a juxtaposition between worry and joy that threaded through the workshop. We spoke of isolation from family during the pandemic, of illness, and worry about politics, unrest, and the struggles of young people. We spoke, too, of hills full of birds, patches of sunlight, time with siblings and parents, forests and adventure and freedom. We then listened to four poems. In selecting them, I thought a lot about the voices I was putting into conversation – like the participants, they were people who likely would never have met in person. Taken together, these poems evoked the pandemic, the movements for racial and social justice, and connections to nature. During the pandemic, the first poem, by Derek Mahon, had provided comfort to many people in and outside of Ireland. Mahon recently passed away at the age of 78 after a career that flourished during his 60s and 70s (a reminder that beautiful work takes time). Everything is Going to be Alright By, Derek Mahon How should I not be glad to contemplate the clouds clearing beyond the dormer window and a high tide reflected on the ceiling? There will be dying, there will be dying, but there is no need to go into that. The poems flow from the hand unbidden and the hidden source is the watchful heart. The sun rises in spite of everything and the far cities are beautiful and bright. I lie here in a riot of sunlight watching the day break and the clouds flying. Everything is going to be all right. I thought of this poem as the first one in the sequence, but perhaps it would have been better as the last. One participant felt angry on first hearing it – that everything is not going to be ok. But, she ended her reflection with a feeling of acceptance and the idea that life will continue on earth regardless of what humans do. I had also shared this poem with my students at George Washington University, and one of them shared that it gave him comfort just to hear someone say out loud that things will be ok. To me, the second poem followed naturally from the first because it was explicitly intended to recognize sacrifice and loss due to the pandemic, but also because of the vivid nature imagery woven throughout. Silence By, SM A moment of silence for the frontline workers risking their lives and those we have lost to COVID-19 Silence! Close your eyes, inhale the essence of fresh air And picture yourself floating on a cloud that heals your heart – Cleanses your soul Silence! Picture yourself dancing in the rain Ecstatic of overcoming uncertainty Silence! Picture yourself in the wake of a thunderstorm – Sun breaking, rainbow in the sky Silence! Feel yourself at the ocean’s shore Listening to the screaming waves Silence! Feel yourself at the riverbank Anticipating going for a swim Silence! Breathe for the ones we lost – Let your heartbeat carry their legacies over the hills of the valley Through strong winds and under the sky of their heavenly home Silence! Kisses to the mothers, hugs to the fathers – Gone but never forgotten Silence! Exhale and breathe life back into the world. When I think of a moment of silence, I think of emptying the clutter in my mind or of concentrating on those we have lost. Instead, SM fills that small space with an abundance of cleansing, wild, water imagery that must contrast sharply with daily life in a confined place absent of both wind and water. This poem, written by SM, was posted on the Free Minds Book Club website. SM is a currently incarcerated person. The website mentions that the poets welcome comments on their work - please consider supporting their work or commenting on that site if you appreciate this poem. Like the poem by Derek Mahon, the next poem has been widely circulated this year, this time in the context of the protests for racial justice. Ross Gay wrote it some years ago. A Small Needful Fact By, Ross Gay Is that Eric Garner worked for some time for the Parks and Rec. Horticultural Department, which means, perhaps, that with his very large hands, perhaps, in all likelihood, he put gently into the earth some plants which, most likely, some of them, in all likelihood, continue to grow, continue to do what such plants do, like house and feed small and necessary creatures, like being pleasant to touch and smell, like converting sunlight into food, like making it easier for us to breathe. What first drew me to this poem is the shocking contrast between Garner’s brutal death and the gently slow nurturing of gardening. The poet, Ross Gay, has spoken of being a gardener himself: “I’ve been gardening a lot, working in community with people in a place. It has helped me to think differently.” Often, outside of agricultural and educational contexts, I think more about gardening as a solitary activity – a way of connecting with the earth and nature and sources of food, but not with other people. But then, I imagine community gardens as such places of shared labor and joy. I chose the last poem because of the ideas contained within it about freedom as the ability to wander in nature. It is from the book, Sparrow Envy, and the poet, Drew Lanham, is a biologist, environmentalist, birder, professor, and writer. As a Black man, he has written for years about the joys and perils of birding while black – an activity that gained attention this year because of Christian Cooper’s incident in Central Park. Wild Wishes Beyond Widgets By Drew Lanham Real world means inside obligations to tend to. Widget making. Deadlines pressing. Bills always due. More and more four walls feels like a trap – a cage with no escape. Not being out; not wandering somewhere wild – seems sinful. There’s something wonderful I’m not witnessing. Some bird or beast flies or creeps by as I stare into someone else’s expectational chasm. It’s an expanse I’m increasingly unwilling to span. A new sun warms in brilliant hues. The same tiring orb sinks into the abysmal blue. Wen that coming and going cycles absent my first-hand witness, I’m squandering time. If wildness is a wish then I’m rubbing the lamp hard for a million more wandering moments. I’ve been listening to Lanham’s words a lot lately, especially through talks sponsored by the North American Association for Environmental Education. In digging a bit more, I found this richly evocative place description, “Drew and his family live in the Upstate of South Carolina, a soaring hawk's downhill glide from the southern Appalachian escarpment that the Cherokee once called the Blue Wall.” In selecting poems by Lanham and Ross, I had been thinking about something along the lines of what Rebekah Sager wrote yesterday in an article about her single father: “I am exhausted by the overwhelming number of negative images I see of Black men. Constant and unyielding videos of Black men being shot, sitting on curbs in handcuffs, or their faces smashed into the asphalt. We rarely see them as regular men. Cooking dinner. Going to work. Just being fathers and loving their children.” The voices and images in these poems have helped lift me up over the past few months. I hope that putting them in conversation provides a tempered sort of hope – there is dying and there is injustice, but there is much beauty and possibility and creativity. Although I have been listening to these poems and thinking about these ideas, I had not done any reflective writing that was specifically about these poems until today. During the workshop, I kept returning to the idea of breath, taken away by force or air pollution or anxiety, restored by newly planted trees or by laughter with friends. Through the workshop, I gained even more nourishment through speaking about these ideas with people from different places and different facets of my life. They added their own reflections and poems and a recently written song. We spoke of surrender and loss and healing and slowness and persistence and new life. There was much openness and warmth. It made me feel more certain that in writing, in nature, and in community, we can find hope amidst and in spite of despair. Naamal De Silva and Portia Sampson Knapp Voices Uniting Screams and Cries blend and transform BlackBirds sing spread wings - By, Portia Sampson Knapp, July 2020 Portia in Canada. Photo courtesy of Portia Sampson-Knapp. Naamal: I first met Portia over a year ago at a Women’s Environmental Leadership (WEL) Initiative dinner hosted by the Anacostia Community Museum. The dinner was in a beautiful and strange gothic room within the Smithsonian Castle. Arched windows framed stuffed ducks arranged as though in flight. A stuffed lynx stared down at us from a warm brownstone wall. The night was warm and felt filled with possibility. I re-connected with friends and met a few new people with whom I’ve stayed in touch, including Portia. Over the past two years, WEL has provided me with abundant inspiration and opportunities to connect with inspiring women. In the midst of a pandemic, it gives me joy to remember sharing a dinner and conversation with 30 or so people outside of my family. In dark times, such inspiration is vital, and I am grateful to Katrina Lashley and her colleagues.

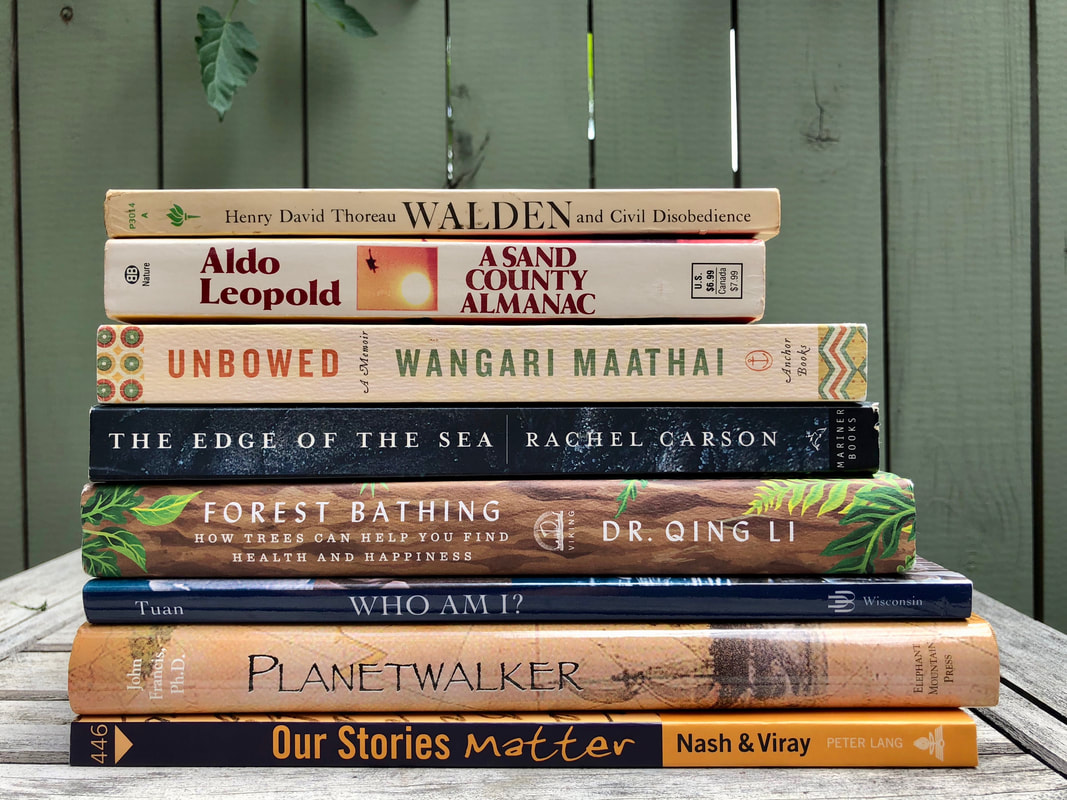

A few weeks after we met, Portia attended a writing group meeting that I co-hosted with Priya Parrotta. In inviting people to the meeting, I wrote “We will discuss how music can shape our stories. I would love for us to work towards writing something - a poem, a journal entry, a song, a blog post. Stories, including music, are a means of inquiring into and understanding life and our place in the world.” During the meeting, we spoke and wrote about music in our lives and related to our connection to nature. Over the summer, Portia and I re-connected through a series of emails about life during the pandemic and the renewed movement for racial justice. Reading and reflective writing has helped both of us during this time. Portia: I've been really devastated and also hopeful. There is new attention from what feels like a larger audience in regard to the systemic racism and violence in this country. I myself have increased my exposure and have found two things: 1) Leaning into the grief has me growing and healing and even connecting more with people. 2) My own self-confidence increases the more I observe and learn about my own history. It's been painful and healing all at the same time, and I'm grateful that it seems the majority of our country does have some understanding of the injustice and wants to see change. Naamal: Soon after this email, she sent me a poem. Portia: It's been very hard, despite the lack of time constraint, to focus long enough to delve into my feelings and use them to create. I was able to squeeze enough creativity out of me for a single haiku. Hopefully this is the start of more. Voices Uniting Screams and Cries blend and transform BlackBirds sing spread wings Naamal: We also did an interview over email, where I asked some questions about her relationship with nature. Naamal: Where are you from? What was your relationship with nature like as a child? Portia: I'm from Philadelphia, PA. Despite growing up in the city, I was raised with a love of nature. Both of my parents are career environmentalists who took me camping and sent me to an elementary school in the woods. I loved sleep away camp and eventually attended and then worked for a wilderness canoe program. I can remember when I was VERY little, of all things, having a real love of earthworms. Though they elicit a strong "ick" factor, I was drawn to their gentle nature. After rainstorms, I picked drying worms off the pavement and tossed them lightly into the grass and dirt in an attempt to save them. I held this habit heavily up through high school, and I still do it on occasion today. Because of this and other examples, I think it was a love of animals and a desire to connect with them that opened the door for me to the natural world. Naamal: I love the story about the worms! I’ve seen so many young children in programs like FoodPrints be drawn in by disgust and then, at least in some cases, switch to fascination and care. Even when they stick to disgust, there is a connection to nature. What inspires you to protect nature? Portia: What inspires me to protect nature? Where to even begin? There is something very healing about being outside and in communion with the woods, water, mountains, desert... Every day, our culture invents incredible technology that serves a purpose and simultaneously pulls us away from this medicine. Nature allows us to be present, to slow down, and listen and feel, to confront our traumas and demons that, like it or not, make us who we are today. Being in nature is centering. Protecting nature is also about survival. My Dad once told me that being an environmentalist was not about saving the planet. "The planet will take care of itself," he said. "Protecting the environment is about the survival of the human species." I also believe we have a responsibility to preserve the land and creatures around us to the best of our ability, and we often fail them when serving ourselves ease and luxury. Naamal: How do you protect nature? How would you like to do so in the future? Portia: I vote. I try to share my love for the outdoors with others. In my 20s, I led wilderness canoe trips for young people. In the future, I would like to find ways to spread this kind of exposure. I think there's no better way to teach appreciation than to take people outside and teach them about it, be it for 10 minutes or 10 days. Naamal: What renews you? Portia: There is nothing better than being still outside and just listening, feeling, smelling, and observing nature. I LOVE a multi-night deep wilderness camping trip. Overcoming moments of discomfort is an essential part of the process. Naamal: What worries you? Portia: That our love for technology will pull us so far away from the outdoors that we will no longer appreciate nature. In the process, we'd lose an essential part of ourselves. Naamal: What gives you hope? Portia: The fact that there are so many people under the age of 40 who have grown up during the era of the internet and social media that seem to love rustic, outdoor experiences. I hope that we teach our children the same. Naamal: Who inspires you? Personally? Professionally? Portia: Jane Goodall has always been a huge inspiration for me. What a humble adventurer whose love of animals and their habitats became her life's mission. She defied the perceived odds for an English woman who at the time had no formal scientific training and changed the face of science as it relates to animals, primates and humans in particular. I think we'd be well served to have more people with her tenacity, confidence, passion, and respect for the natural world. Naamal: I have so many more questions, but this is a start. Each piece of what Portia spoke of could have been a blog post, but no single story can create a portrait of Portia in this moment in time. No single story could possibly capture her over time. Nevertheless, I love the idea of an accumulation of stories that, when considered collectively, help us to understand ourselves and each other. Even in the best of times, I focus too much on wounds to society and nature. Since the spring, I have cycled rapidly through hope and despair. In this time, I find myself leaning even more than usual on the stories of people working to heal our collective wounds. I gather these stories mostly through confidential interviews for consulting work. I hold on to the stories and think with them. It’s a pleasure to share one more publicly. You can connect with Portia on LinkedIn. Naamal De Silva Whose stories are on your shelf? Who's stories do you follow on social media? What personal stories about the environment have influenced your work and your life? It is nearly 4am on Wednesday and I’ve been awake for awhile. I feel consumed. Last week, I felt consumed by the news and by social media. The #blacklivesmatter protests are painful and hopeful and transformative. Between the pandemic and these protests, life and society appear to be changing so rapidly. There is such uncertainty. I am terrified that the stories that have become newly visible to so many will once again be covered over, that our progress will erode away into nearly nothing. I care deeply about diversity, both cultural and biological. My entire life, I have felt that much of what I value is invisible to many people, at least to most people with power to create change. In this moment, if feels like that might change. I have such hope that we are about to move towards a time of justice, greater equality, protection for the vulnerable, and greater care for each other and for the planet. I have hope, but I am afraid that I will end up heartbroken.

Last year, witnessing the global climate protests and Greta Thunberg’s rise, I felt hopeful that we were moving forward towards broader understanding about environmental problems, and that our understanding would extend towards an understanding of the unjust impacts of climate change. I had hope that the anger of children would move us more rapidly towards solutions and towards justice. I hoped that, within and outside of the environmental field, we would see more stories of young people of all colors, nations, orientations, shapes, abilities, and religions. Since the climate strikes have become digital because of the pandemic, it feels as though a lot of that that energy and attention have dissipated. We cannot afford to look away. Climate change and biodiversity loss pose threats to our existence, just as police brutality poses a threat to the existence of black people in America. It will take all of us to address systemic racism in America. It will take all of us to protect vulnerable groups of people throughout the world. It will take all of us to address the climate crisis, species extinction, and plastic pollution. It will take all of us to ensure that the impacts of social and environmental problems are distributed equitably throughout society. To engage and enrage and inspire all of us, it will take the individual stories and emotion and the passionate dedication of a diversity of people. The stories of these people need to be more visible. Throughout my adult life, I have sought stories of the diversity of people working for the environment. I knew that the environmental field was not only composed of the white and the privileged – it only felt that way because the brown and poor were invisible. I searched for stories, but I felt that I was sifting through sand. I looked for these stories in books, in the mainstream media, and in academic journals. I did not find nearly enough. A few years ago, I found far more through social media. I sifted, and I started following accounts of people who spoke out about how they belonged in nature – accounts like those of Rue Mapp and Jenny Bruso and of organizations like Outdoor Afro, Unlikely Hikers, and Melanin Basecamp. I learned about more stories by attending events and meeting people. I found even more through my dissertation research and reading. I gathered some stories by chance - my path to Maya Hall’s story started with trying on a jacket at a Patagonia store. I started a writing group for Mayla and people shared unexpected things. Finding these people and their stories felt like validation. I started Mayla because I felt the need to gather and amplify these voice – the voices of diverse people who care for the environment. I intended to include the stories of white people alongside the stories of black, brown, and indigenous people from all over the world. However, the stories of white people always felt easier to find. I wanted all the stories, but I was looking for the ones that appeared to be rare. That is why I feel consumed right now. Over the past week, it has been so much easier to find stories of diversity. I have been digging deeper into the lives and stories of those who are #blackinnature. These stories bring me joy, even when they express anger. They are some of the stories for which I have been searching my entire life, and suddenly, it feels like I am inundated. I can’t seem to get enough. They are stories that feel intimately familiar, and yet, they are not my stories. They are the stories of people who surrounded me as I was growing up, of people who were friends or who are friends. They are the stories of authors who have influenced my life and how I see the world. They are stories of people who share my skin color but not my history. I have many stories of feeling invisible, and a few stories of feeling like I stand out or don’t belong simply based on my color. The stories of black Americans help me feel more visible. At the same time, they highlight my differences. When I am alone in nature, there have been times when I felt unsafe because I am a woman. There are very few instances where I felt unsafe because I am brown. I can recall one summer afternoon in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, my white husband and I were walking along a forested creek, where a group of white men pulled up with lots of beer and a confederate flag flying from the back of their pickup truck. They did not say anything to us, but as an interracial couple, we felt intimidated, and we left. They took up the space we ceded. As we left, we noticed a large Latino family on the far side of the pickup truck; they were the only other people there and they did not give up their right to enjoy time in nature. Maybe we did not need to do so either. There are far more instances when I have felt protected by my invisibility. In high school, I studied a lot and followed most rules, but I would leave if I felt that I was not learning anything. Two of my history teachers were often missing; my world geography teacher read a newspaper during class while a group of boys played poker in the back of the room. I felt a sense of freedom in leaving, but little fear about cutting class. As I left the building, there would always be police cars around my mostly black school in my mostly white neighborhood. Police officers would be standing by these cars, and I saw them stop black and Latino teenagers. They mostly stopped boys, but a few girls too. They would return these students to the school building. They never once stopped me – they hardly ever even looked at me. It was as though they could not see me, as though my glasses and my South Asian face and my silence were a shield. In those moments, invisibility felt like power. In my career, I have felt at times that invisibility has held me back. I have, at times, attributed disparities in pay or recognition to my gender or my age or my skin color. Certainly, there have been many times in conference rooms where I have made a point that the rest of the people in the room ignored until it was repeated by a white man. There have also been many times when white men have amplified my voice and supported my work, whether through empowering me to publish articles or through opening doors that might otherwise remain closed despite my education and experience. I am a brown woman in conservation – sometimes that makes me invisible and at other times it makes me stand out. Nevertheless, I have not had to think about whether my hairstyle would keep me from a promotion. I have never wondered whether I might be arrested or possibly killed for walking in a park. Amidst the deluge of stories this week, I keep returning to that of Christian Cooper, whose care for the lives and wellbeing of birds posed a direct threat to his own life and wellbeing. We all needed to hear his story, but not just the story of his encounter with Amy Cooper. We all need to hear stories of the diversity of people who care about nature. It is through stories that we make meaning of what is happening in the world. Through stories, we process loss, whether it is the loss of a human life at the hands of the police, or of a nearly extinct shark at the hands of fishermen. We need the stories of the people who resist injustice and who halt extinction. We need MORE stories of black and brown and indigenous and white scientists and activists and innovators and farmers who are passionate and visionary. We need to feel their pain and anger and joy, to hear about their ancestors and home places and sources of inspiration. We need their creative solutions and unique perspectives. We need to see the ways in which racism and injustice limit our collective access to creativity, innovation, and care for the earth. We need their stories and their work to be visible so that, together, we can envision a future that is both just and sustainable. Naamal De Silva This mural by Aniekan Udofia is outside the Rumsey Aquatic Center in the Eastern Market Neighborhood of Washington, DC. It has inspired me for years. After feeling increasingly hopeless yesterday, I woke up this morning enthusiastic about centering the voices of African Americans in a series of blog posts – I thought of specific stories and of specific people who have inspired and influenced me throughout my life. I have so many ideas. I want to amplify black voices and have wanted to do so for many years. But what does that mean? What does that statement truly require from me and from other people and institutions intending to make that commitment? What are the costs, what are we willing to invest, and what are some ways to move beyond the hashtags? The hashtag #amplifyblackvoices resonates strongly with me, but the hashtag by itself will not create systemic change.

To move beyond the hashtags, we have to think first about why we want to amplify black voices. Is it because of personal guilt and pain about racism? Is it to seek sources of reconciliation and healing and joy? Is it to find different ways of knowing or to find hidden solutions? Whose voices, in particular, do we want to amplify? How will such amplification benefit those people? How might we benefit? Reflection and reading always help me work through such questions. Next, consider time - our own time and especially the time of people whose voices we intend to amplify. I identify as a brown woman, an American, and an immigrant, a Sri Lankan; I am so much more than those labels, but I am not African American. If I want to find and share a range of black perspectives, I am asking for the time and energy of people who might have very little of both. If we are not ourselves African American or part of the African diaspora, amplifying black voices could include sharing what black people have already created and shared publicly. If we want more than that, and in many cases, we should want more, then we are asking for a commitment of time and creativity and brain power. If we intend to amplify voices other than the comparatively few who already have a platform from which to speak, we will have to request interviews or essays or poems or songs or videos. Over the past several years, I have been doing just that. I have been asking a diversity of people for their personal stories about protecting and connecting with nature. I have been searching for people with diverse backgrounds and experiences because I believe that a more complex and nuanced understanding of the environment and each other will lead to more productive and meaningful work. I have asked for the perspectives of those who differ from me in terms of ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexuality, class, and myriad other facets of identity and experience. In asking for their stories, I have not provided any financial compensation to any of these individuals - not because I did not want to or did not think to do so, but because I had no funding to offer. Despite that lack of compensation, I’ve benefited from their ideas and their stories have enriched my life and work. Some people I asked have wondered what they had to share that would be of value to others. They have told me that what they do is not special or unusual. They have told me that they are only volunteers, not professionals. They have told me that they are not experts. In each of those cases, I can’t help feeling that there is a long history of silencing and invisibility behind those beliefs – a personal history but likely also an intergenerational history. In those cases, I have found wealth and class and education to be bigger barriers than race. What can we do? In some cases, nothing - not everyone wants to stand on a stage. In other cases, find and hire those passionate and inspiring individuals so that they become professionals rather than volunteers. Invest in education and in creating opportunities for more black, indigenous, and brown people to become experts. Invest in management training and in leadership training. Many of the people whom I asked for stories responded with enthusiasm. They have attended writing group meetings and salons, spoken in the class I teach at George Washington University, mentored young people, exchanged emails, or had conversations with me about what they hope to share in the future. I’ve interviewed people for my dissertation, for my blog, and for my consulting work. These individuals have told me that these interactions have been meaningful. Is that enough? Despite their enthusiasm and generosity, most of the people I’ve asked are tired and have little time outside of work and parenting and other obligations to reflect or write or complete blog posts. Despite years of such conversations, very few of their stories end up on my website. As has become glaringly visible this week, African Americans tired of carrying the additional and heavy burden of systemic racism. So many people of all races who do environmental and social justice work are tired. They are burdened by enormous obstacles, public apathy, and limited resources. Many also carry the burdens of being unpaid or underpaid. They are tired because, in addition to their internships or volunteer work, they need to take on additional jobs in retail or restaurants that do not adequately utilize their skills and education. If, as in too many cases, they cannot move on to better paid roles or rely on their families for financial support, they may need to abandon their efforts to protect society and nature. Many leaders of organizations devoted to social justice, poverty alleviation, education, and the environment cannot afford to adequately compensate their employees and have to compete for scarce resources. If they are people of color, and especially if they are black or indigenous, they are far less likely to win. They are tired. We are tired. I am tired. It should not be such a struggle to meaningfully engage a diversity of voices and perspectives. We should not have to be at a point where we need to say that black lives matter or to implore each other to amplify black voices. This exhaustion is not sustainable, and because of exhaustion, so many people do not publicly celebrate their successes or share their perspectives. So what, then, is my own commitment to amplifying black voices? I do not yet have the funding to pay for articles or interns for Mayla. I can commit to writing more about what I have seen and heard about the experiences of African Americans. I can ask to share what people have already written on their own blogs and social media pages and websites. I can continue to encourage black people to share their own stories. I can do all of these things and more. But, how do I address the broader forces that maintain the silence and invisibility of black and brown voices? Phrased another way, how do I amplify black voices and share diverse stories without contributing to exploitation and without myself being exploited? Part of what exhausted me yesterday was seeing a wave of posts on Instagram where African Americans in the arts and in the environmental field highlighted the importance of being financially compensated for intellectual property and creativity. In those posts, I couldn’t help but notice the stain of a legacy of exploitation that stretches back centuries. How can we move beyond exploitation? Financial compensation is only part of the work to amplify black voices, but it is an important part of the work. I often hesitate to ask people for their stories or their involvement with Mayla because I want to be able to compensate them financially. I have no interns or staff or fellows, though I could find many who would effectively expand the work that I do. If people make too little money through their work, how will they have the creative freedom to share their stories? In America, there is abundant research that shows that black people (on average) make less than white people do, and that difference is more stark for black women. On average, if a white man and a black woman begin working on January 1st, the black woman will need to work throughout year and into August of the following year to earn what the white man makes at the end of December. This is a systemic problem and requires institutional work on the part of nonprofits, corporations, and the government. The exploitation is not purely financial. Within the environmental and international development fields, the photographic exploitation of black and brown bodies is particularly prevalent. I have written about this before using my own experiences. I continue to be amazed at the ability of conservation organizations to raise money for the work of primarily white people by using the smiling images of poor black and brown people. This needs to change. Conservation and development photographers need to ask permission of black and brown parents before photographing their children; if those parents are not with their children because they are plowing their fields, they might reconsider whether they capture the image at all. These photographers need to ask for the stories and names of the people they photograph so that we no longer end up with broad general statements about entire groups of people. It is time that environmental and development organizations finally move away from the myth of the noble savage. We need to amplify specific and individual voices of the black and brown and indigenous and poor. In particular, I believe we must amplify the diverse voices of people working to improve the environment. Next time you are creating your annual report, consider replacing that unknown smiling black face with the specific story of a black or brown person who is a colleague or partner. Consider hiring a black or brown photographer to take those photographs so that you have something better than a grainy image taken in a conference room. Better yet, include black or brown staff members and board members and partners in creating the vision and mission and strategy and metrics that guide your work. These are many very specific ways in which organizations can move from hashtags to empowerment. How do we ethically amplify black voices? Find diverse stories, including by and about black people. Read widely. Reflect, question, and share. Engage a diversity of people in your work. Include black people in creating your vision, your goals, and your proposed actions.Compensate black people for their time and input. Invest in their personal goals. Ask them to share their own stories. Repeat. Let’s continue to call for amplifying black voices and for amplifying the voices of indigenous people and countless others who have been left out of the conversation and who remain invisible. Let’s also focus on systemic change that prevents further exploitation. Resources The articles I referenced in this post, in order: Racial bias in philanthropic funding for environmental and social justice - an article by Cheryl Dorsey, Peter Kim, Cora Daniels, Lyell Sakaue & Britt Savage in Stanford Social Innovation Review. The wage gap by gender and race - an article by Sonam Sheth, Shayanne Gal and Madison Hoff View people as individuals rather than representatives of their ethnicity or nationality – an article by me on the Mayla website A history of racism in the environmental movement – an article in Vice by Julian Brave NoiseCat. A brief list of relevant blogs and websites and social media pages by and/or about black voices for the environment: Outdoor Afro and founder Rue Mapp Our Climate Voices and work on grassroots climate solutions Echoing Green and president Cheryl Dorsey Green 2.0 and Whitney Thome The Anacostia Community Museum and especially work by Katrina Lashley on Women’s Environmental Leadership The Black & Project by Amanda Bonam These are some of the people and organizations that have been on my mind this week, but there are so many more, and I strongly believe that it is our responsibility to look beyond the few stories and organizations that are most visible. We must look for and amplify diverse people and stories relevant to the places where we live and work. Since the problems and solutions are local and global, we must also push ourselves to move ever outward from familiar places and perspectives. Look inward – at your own heart and your own past experiences and your own community. Look outward – to the stories of black and indigenous people in other parts of your state or province, your nation, and in other nations. Naamal De Silva A couple of weeks ago, I read a wonderful article about creating comfort during the pandemic. The author, Isabel Gillies, wrote that, in a time of fear and anxiety, it helps to focus on the little, cozy things. Coziness suggests warmth and comfort, and we could all use more of both right now. I asked the Mayla Facebook community about what has sustained them during the pandemic. The replies: baby smiles, chickens, woodland trails, gardening, volunteering, reflection, video calls with friends, sunshine, writing poetry, healing patients, listening to music. There are so many sources of comfort. I am sustained by the Schefflera plant that has accompanied me from home to home for over twenty years, by the bees and birds feasting on the Eastern Redbud tree outside my window, by homemade bread, and by conversations with family. For me, comfort is my grandmother’s sari – the silk has a few holes, but they are filled in with memories. Coziness is the red chair in my living room - faded and a bit stained but so much softer than it was a decade ago. There are so many beautiful new saris and endless options for replacing that chair, but none would hold the same meaning. Thinking more broadly, coziness is, I think, one of the many things we give up in our quest for newer, bigger, and better. Our search for what is new can strip life of coziness and comfort. This week marks 50 years since the first Earth Day – a call to care more for the environment. Too few people heard that call, or the calls of many others who have spread a message of care for hundreds or thousands of years. Globally, our never-ending consumption of clothes, furniture, and houses is unsustainable. It results in overflowing landfills, eroding hillsides, homeless tigers, red rivers, illiterate children using tiny hands to tie even smaller knots. As I stay close to home and walk around and around my neighborhood, I've been thinking about what feels cozy. Some of the newly renovated houses in my neighborhood feel sterile and generic, washed clean of the stain of years of comparative poverty, but also stripped of layers of joy and love and tears. There is less life, and the houses have shed the softness of age. The paint is new and often gray. If you pass by in the evening, you might get a glimpse of cool bluish down lights and newly opened up floor plans. Their manicured gardens have trimmed hedges but no dandelions for the bees. No one is sitting on the stoops chatting. There is no music drifting from open windows. As city neighborhoods fill with new wealth, they lose some of the communal ties that make life comforting. Words like gentrification and displacement do not adequately capture these losses. Even during the pandemic, the constant noise of construction underpins the songs of birds. The waste generated by all this renewal is largely invisible. During one recent walk, I was captivated by an old porch. It made me think of lazy summer afternoons. I loved that, unlike a lot of the houses around it, it showed its age. Somehow, it also specifically reminded me of summer afternoons during childhood vacations to Sri Lanka - a feeling that held within it both freedom and rootedness. In those afternoons, I felt nourished by old houses and old people and old trees. In this time of staying close to home, I was happy to encounter an unexpected connection to another time and place. Over the upcoming months and years, I worry that the pandemic will bring with it an even stronger global drive towards the sterile, the virtual, and the new. This is not the time to buy used things or to donate what you no longer need. This is the time of disposable protective gear - and there is not nearly enough of it to protect those who care for the rest of us. The pandemic has created massive upheaval, and I wonder what changes will last. I wonder how many plastic gloves and bags will be drifting in the ocean in a year, about how many gallons of milk farmers will have poured down drains. I worry that relationships may fray. I fear for the leaching away of small and local and sustainable businesses. And, of course, I worry that there could be less money for protecting both nature and human rights. Nevertheless, there is hope too. I love the stories of how people in New Delhi are seeing consistently blue skies for the first time in many years, about how people are able to breathe more freely. The maps contrasting air pollution now to last month are striking. More people around the world are noticing the birds and insects around them. There are stories of wild animals roaming the streets of villages and cities, likely in part because animals are venturing further into human habitats and in part because more people are looking for them. So many of the beings with whom we share this world might be feeling lower levels of stress even as we humans are feeling more – there is less noise in the skies and in the seas, the ground trembles less. They, our neighbors, might feel a sense of relief, a sense of comfort, and maybe even something like coziness. But their sense of ease is probably temporary, a brief respite from the seemingly endless hunger of humans. In this moment, hope and despair feel tightly intertwined. As many of us move beyond staying at home, will we be able to regain some ease while maintaining a better balance with nature? How can we retain a sense of the small and cozy while moving back towards what we consider "normal"? I wonder if part of the answer to these questions lies in a shift in perception towards valuing what already is, in reframing our collective definitions of progress. This year, our Earth Day celebrations will, by necessity, have to be more intimate – more cozy. These more intimate celebrations and actions, coupled with virtual global connections, could provide inspiration for a more personal approach to caring for the environment. In the opening sentence of her book about creating comfort, Isabel Gillies questions whether coziness can possibly matter on "a planet where people are hungry and elephants endangered." But, she says that being cozy helps her "feel capable of getting through to the next moment, to help another, to accomplish something important.” As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day, I think that could be true for all of us. If we invest more in understanding and valuing our own comfort, we might be better able to consider and fight for the comfort of all beings. Naamal De Silva A pandemic makes visible the connections between all of us. For perhaps two weeks, one of my rituals has been to look once a day at the maps compiled by the New York Times – maps of the places with reported COVID-19 cases. There is one map for states in the U.S. and one map for the world. The first time I looked, there were no cases reported in Africa. I wondered whether the gaps on the map had to do with testing or whether there were fewer strands of connection between many African nations and the rest of the world. Over a shockingly short time, the countries and American states filled in. West Virginia became the only state without reported cases – again I wondered whether this was due to comparative isolation or to lags in testing. Papua New Guinea became one of the only places on the world map without reported cases. Both places are mountainous and comparatively poor economically - isolation that has enabled cultural richness and the persistence of biodiverse landscapes. I am fortunate to have visited both places. In the past, I have been concerned about environmental damage in both places – from mining, oil palm expansion, a lack of strict regulation and capacity for monitoring. I have thought about new jobs being primarily in extractive industries, and read about the potential for renewable energy and ecotourism. This week, I worried about how such relatively isolated places will cope with the spread of a disease that thrives on social connection. I thought, too, that if people did not travel quite so much for work or leisure, COVID-19 would not have spread to some parts of the planet for years – enough time to have found a vaccine and better treatment options, for richer nations to recover and consider lending a helping hand to nations with fewer resources. I have been thinking, more generally, about isolation and connection. In my household, we have been isolating ourselves from people outside our home, but in doing so, we are more constantly connected to each other. I am accustomed to working from home, but my husband is not; he has been adjusting over the past week. My daughter has not been in school for over a week, and it will likely be many more before she returns. I am adjusting to having them near me all the time. I have been making sure that we go out into nature most days for connection to other beings and the outdoors, even as we maintain some distance from other people. Even when we feel exhausted or upset, I know time outdoors will help us. Our more constant connection makes me chafe at times, especially thinking about weeks of limited mobility. At the same time, I feel lucky for their presence in my life. I feel fortunate that we can retreat to different rooms or to our tiny deck. I feel lucky to be alive, acutely so in a time when I know I am at some level of risk due to asthma and a history of pneumonia. I feel lucky that my husband and I both still have work and that we derive meaning from our work, that most of our friends and family are healthy. Really, the list of things to be grateful for is endless, existing alongside middle-of-the-night anxiety and a constantly shifting sociopolitical landscape. As Lori Gottlieb wrote recently in The Atlantic, it is "BOTH/AND: It’s horrible AND we can allow our souls to breathe.” I have been thinking, too, about the role that connection and isolation play in our relationship with the environment. The pandemic shines a spotlight on many things. It confirms what I have long suspected: in times of acute crisis, humans are capable of rapid shifts in behavior. It is remarkable how many business leaders were able to cancel travel across the globe. It is remarkable how drastically our carbon emissions have dropped during this time of less travel. Still, we cannot stay inside our homes forever, and so many of us do not have that luxury even now. How can we find a more effective balance between connection and isolation, between a frenetic push for progress and paralysis? How can we use this pandemic as an opportunity to create systems that better support our collective health and wellbeing? How can we create places and ways of living and working that will be resilient in the face of future pandemics and a changing climate? How can we create a greater sense of community and meaningful connection to each other in an increasingly digital world? The pandemic is terrifying. I worry for people I know personally and for billions I will never meet. There is no getting around that. However, if we collectively decide that the threats facing us are existential, I believe we will defeat COVID-19 and be better prepared for future pandemics. I believer that we can create new ways of being that increase our resilience in the face of climate change while actively fighting the poisoning, weakening, and impoverishment of our environment. We can more intentionally decide what travel is necessary, what industries serve the collective good, where each of us spends our time and money and effort. We can choose collective action, health, gratitude, and joy. We can choose rest and recovery – for ourselves and for the planet. Sometimes, a pause and reset is exactly what we need to create new ways of being. by, Sheldon Cohen My name is Sheldon Cohen. I have a type of cancer called leukemia. Our planet also has a cancer - it’s called climate change. During my 35 years working on environmental conservation all over the world, I’ve witnessed firsthand dying coral reefs, burnt-over forests, and dried up lakes - due in part to climate change. And I’ve witnessed people suffering from the early impacts of climate change. These realities have shaken the very foundations of my life and have inspired a recent decision to dedicate my remaining years to the fight against climate change. Teaming up with my son (Zachary), through creative actions, videos, original songs, public speaking, and reducing our own carbon footprints, we intend to catalyze climate action by harnessing the power of compassion. Regardless of ideology, political party or other labels, as members of the human family, we all feel compassion for the suffering of people currently impacted by climate change. We feel compassion when we realize that climate change could harm our children, grandchildren, and future generations. We can also feel compassion for the impacts climate change is having on the natural world and other life on Earth. This heart-based approach, with compassion building bridges and bringing us together, draws on my 20+ years of Buddhist practice. Working together, as part of the growing climate change movement, we can achieve our shared vision: Soon To Be, Carbon Free. In May, Sheldon started a Facebook group called Catalyzing Climate Action. He welcomes new members and connections to other individuals and groups, especially youth-led initiatives. In his group, Sheldon has been documenting his journey to expand beyond his marine conservation work and into climate activism based on compassion and open heartedness. Sheldon wrote and recorded “Soon To Be, Carbon Free” with his family. His wife sings the harmonies and his son produced the video. Sheldon describes the song as “a heart-based alarm bell, call for action, and message of hope” and hopes that people will sing along and share it widely. He followed the song with a brief story of “how a long career in the environment field, a cancer diagnosis, and compassion for my friends, family and future generations inspired the recent decision to dedicate my remaining years to the fight against climate change. I have taken a Carbon-free Pledge to take immediate actions and am calling on others to also take this Pledge.” On Friday morning, Sheldon issued a Call to Action, suggesting four types of actions that we can all take together to help solve the climate crisis. For more information, Sheldon suggests the following:

First, an animated video. In about 10 minutes, it covers basic information about the causes of climate change, calculating your carbon footprint, and specific individual actions to reduce your carbon footprint. Some actions are specific to temperate climates, and some statistics are specific to British Columbia, in Canada. Four universities, working together through the Pacific Institute for Climate Solutions (PICS), created this video. Next, a clearly written article by Diego Arguedas Ortiz that highlights actions individuals can take in the context of the systemic, policy-driven changes that must occur before we can adequately address the climate crisis and related environmental problems. Individual action will not be enough without work by governments and corporations, but such action can engage others and catalyze systemic change. Arguedas Ortiz maintains a global perspective; his article is part of BBC Future. By, Naamal De Silva Two years ago, my brain was buzzing with hashtags about nature and people. I came up with a list, and a good friend added an important one – #WeAreNature. When we feel viscerally that we are part of nature, we want to care for all species as we care for our families, pets, friends, and selves - after all, we are all related. When we perceive ourselves as part of nature, we also see more connections to other humans. In 2019, it feels like fewer and fewer of us notice that we are part of this ecological web of interconnectedness. More and more of us are tangled in the worldwide web. More and more of us live in cities. We are increasingly disconnected from nature, and seeing ourselves as nature could move us back towards connection. More recently, I’ve also been considering how we perceive each other. In particular, I’ve been thinking about how conservationists perceive people. I am a conservationist. I am keenly aware of how this work grows daily in importance as our world becomes hotter and more crowded. At the same time, I am uncomfortable with the social history of conservation. The history, traditions, and methods of conservation facilitate another type of separation between humans and nature. This separation was deliberate, and persists today in far less conscious and obvious ways. In this view, there are people, who are largely responsible for environmental degradation. We are the ones who own corporations, drive cars, and eat mangos in the middle of winter. Sure, there are the few who are vegan, protect coral reefs, and don’t use straws. But, we humans are still responsible and need to feel guilty. Then, there is nature. Nature is awe-inspiring, colorful, fragile, and desperately in need of saving. Nature includes coral reefs, polar bears, poison dart frogs, and majestic redwoods. Nature also includes indigenous people and those who maintain traditional lifestyles. Looking back a few hundred years, this distinction shows up when Europeans collected a few live humans along with their tobacco plants and vividly colored birds. Explorers took these specimens home to impress the royals and nobles who paid for their expeditions. The royals would show them off to their friends. Today, photographers collect images of lush rainforests, vividly colored birds, and smiling villagers to raise money for nonprofit conservation or development organizations. On social media, these photographs tend to have captions or accompanying narratives. In these stories, richer, whiter, more urban people almost always have names. They have first names and last names, and often titles too. They are often depicted with the tools of their trade – camera, clipboard, binoculars. By contrast, the stories almost always refer to indigenous and traditional people by tribe or village. Bejeweled Maasai men look nobly into the distance. Tibetan children smile with impossibly rosy cheeks. A Tanzanian or Tibetan tour guide might be allowed a first name. Their clothes are western, modern – they are human, but barely. I have taken photos of Maasai men and of Tibetan children. When I traveled to distant lands, it was easy to be struck by the beauty of people, their surroundings, and the ways in which they decorate themselves. I was entranced by their differences and their similarities to myself. Throughout the world, lives and places and traditions seemed to be changing so quickly. Photography was one way to hold on and to bear witness to what was fading away. I have taken photos of bare-chested teenagers in Papua New Guinea. I do not know their names. I wish I did. At the time I took the photos of these teenagers, I knew that I would never share these photos without cropping them. But, I did use one or two cropped images of their lovely, smiling faces in PowerPoint presentations. My presentations had more to do with protecting rainforests and reefs than with the lived experiences of these girls. These girls were minors, and I certainly did not have signed waivers from their parents. I did not even know where their parents were. All I saw when I got off a plane in Alotau was a group of excited teenagers wearing skirts made of grasses, their faces painted and weapons at the ready. They danced to welcome people arriving for a conservation conference. They were proud of their performance and pleased to be photographed. I saw them then as I see them now: as teenagers, with all the excitement and anxieties that come with rapid shifts in identity and appearance. I did not see them as “nature,” but I did not talk with them or write down their names. This was 2008. Cameras tended to be digital, but social media was in its infancy. I will not be sharing those photos on this blog post. A few months later, someone in the communications department of my organization categorized me as nature based on a photo. In the photo, I am smiling, squatting in front of the rough wooden boards of a small building, mud on my pants and a flower tucked behind my ear. It’s a portrait that I love, taken by a friend who knew me well. My friend, William Crosse, took this photo on the same trip where I took the photos of the teenagers. He had contributed some of his images to the photo bank of the organization where we both worked at the time. Generally, these images were used without captions on the website, on presentations, and in brochures. This particular image was used in an internal slide show and in a brochure. The brochure was where the sorting happened, and it happened in the captions, which featured some named people (the conservationists, the heroes, the saviors) and some nameless people (the recipients of conservation largesse, those living in harmony with nature, as nature). I was nameless. I was not one of those conservation heroes. Someone had cropped out my digital camera. My smile and my brown skin were being used to sell an old idea about saving faraway, exotic nature and faraway, exotic people. I could imagine a caption for that photo of me: “In the face of accelerating climate change, women from tropical islands struggle to maintain their traditional way of life. Rising sea levels threaten to wash away their ancestral lands. [Insert name of environment or development organization] helps by teaching them how to farm seaweed.” A caption like that would be sort of true. I was born on a tropical island. My grandmother's family lived for generations on coastal land in the village of Thiranagama. That land holds some of my earliest memories, of digging my toes into wet sand, searching for elusive clams while holding on against the tug of the waves. I wonder at times whether rising seas will wash away that land. But, in this particular photo, I was on a very different tropical island. I don’t struggle to maintain a traditional way of life – I was born in one capital city (Colombo) and grew up in another (Washington, DC).  In the face of accelerating climate change, women from tropical islands struggle to maintain their traditional way of life. Rising sea levels threaten to wash away their ancestral lands. [Insert name of environmental or development organization] helps by teaching them how to farm seaweed. Photo by William Crosse. My friend took another photo of me on that trip. In it, I have a camera in front of my face, with a lens large enough to block out my features. I’m sitting on a boat in the middle of a river, with hazy tropical hills behind me. I could imagine a caption for this photo too. “Dr. Naamal De Silva, on a field trip in rural Papua New Guinea in 2008. At the time, she worked with numerous partners to identify globally important sites, species, and landscapes.” Labels are powerful. Labels delineate belonging and community. However, through this very delineation of group identity, they inevitably exclude. Each of us has many labels. The labels we use for ourselves are rarely exactly the labels that others assign to us. Labels also change over time.

Our names, by contrast, are relatively stable. Our names highlight our individuality, and they are markers of our humanity. Taking away our names takes away part of our humanity. Slavery in the United States provides a powerful example of that. I recently saw what might be the first known portrait of a slave, a young woman known only as Flora. While it is a lovely, biophilic name, it is unlikely that “Flora” was what her parents named her, or what she chose for herself. Similarly, during the holocaust, nazis at concentration camps replaced the names of Jews, Roma people, and others with tattooed numbers. Stripping away names, stripping away humanity, facilitates acts of unthinkable brutality. Independent journalism and bearing witness can help prevent or halt genocide and other horrors based on sorting and exclusion. Photography is a vital type of storytelling, and since life is continually unfolding, sometimes it is impossible to ask for names. Sometimes, naming people can compromise their safety or their ability to speak openly. I understand that. And, I believe that conservation photography is vital, since we will not feel moved to protect what we cannot see. While not directly attributable to climate change, a portrait of a starving polar bear made the consequences of climate change feel more viscerally relevant and immediate for billions of people. Portraits of a giant Indonesian bee and a lonely Bolivian toad brought the world’s attention to species that we considered to be lost forever. Portraits of individual humans can similarly highlight diversity, beauty, peril, joy, vulnerability, power, and so much more. Recognizing all of this, I still believe that we can all do better in showcasing people as both part of nature and as humans. Portraits of people should highlight individuals as subjects and not objects – we should feature their humanity alongside their connections to nature. Including full names whenever possible helps showcase both humanity and agency. by Maya HallI finally feel like I am at a point in my life where I can make tangible change. That being said, change is hard. There are many scary things in the world. These scary things sometimes feel impossible overcome. The fear of losing our wildlife and their habitat is something that hangs like a butcher’s knife over my head, and it is petrifying. But, the fear of never doing anything to sway that executioner’s hand, is above all, my greatest fear.

I regularly tell myself that I need to grow up. As a young adult, I need to be brave and push forward into the world of wildlife conservation and environmental science. I tell myself I need to be a force to be reckoned with. I need to be a force that can change the world. But, I ask myself, how do I change the world? How can I make waves in what seems to be a never-ending ocean of shared dreams, aspirations, and goals? How can I become the self-assured, mature scientist I’ve always wanted to be? To be honest, most days I still feel like I am grasping at nothing more than a child’s daydream. To calm these fears, I think back to what started me on this path. Loving wildlife and nature came easily to me. I was very fortunate as a young child to have access to a lake and all the fun nooks and crannies that came along with it. I would dig in the ground for insects and catch minnows in the shallow parts of the lake. I would collect snake skins and tape them into a book along with pressed leaves – a self-made nature book. I would pick wild blueberries and watch dragonflies hunt along the glimmering water. I would bask in the beauty of the natural world, unafraid. I miss this unabashed love of dirt, water, and all things living. Having grown up, I find myself outside less and less. We all have to grow up at some point; this much I know is true. But, what if it is that young, child-like mindset, that wonder, that should remain our lighthouse? Retaining my sense of wonder may help me become the confident and accomplished professional I envision. Perhaps I can embrace and nurture the part of myself that I have chipped away at through competition, academics, and rigid standards – this could be my tool to enact change. What if going back to our roots, back to who we were when we were those open-minded, loving children, is the key to a more sustainable future? To connecting with each other and growing as a community for environmental change? To being fearless in our pursuit of planetary healing? I cannot be certain this is the key, but maybe, just maybe, we shouldn’t grow up so fast. |

Curating Hope features the personal stories of diverse people who protect nature. Together, we can envision a more sustainable future.Archives

November 2020

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed